Garth Paine, Arizona State University

Our hearing tells us of a car approaching from behind, unseen, or a bird in a distant forest. Everything vibrates, and sound passes through and around us all the time. Sound is a critical environmental signifier.

Increasingly, we are learning that humans and animals are not the only organisms that use sound to communicate. So do plants and forests. Plants detect vibrations in a frequency-selective manner, using this “hearing” sense to find water by sending out acoustic emissions and to communicate threats.

We also know that clear verbal communication is critical, but is easily degraded by extraneous sounds, otherwise known as “noise.” Noise is more than an irritant: It also threatens our health. Average city sounds levels of 60 decibels have been shown to increase blood pressure and heart rate and induce stress, with sustained higher amplitudes causing cumulative hearing loss. If this is true for humans, then it might also be true for animals and even plants.

Conservation research puts a heavy emphasis on sight – think of the inspiring vista, or the rare species caught on film with camera traps – but sound is also a critical element of natural systems. I study digital sound and interactive media and co-direct Arizona State University’s Acoustic Ecology Lab. We use sound to advance environmental awareness and stewardship, and provide critical tools for deeper consideration of sound in nature preserves, urban and industrial design.

Arizona State University professor Garth Paine explains the power of listening as a way to experience the natural world.

Sound as a sign of environmental change

Sound is a powerful indicator of environmental degradation and an effective tool for developing more sustainable ecosystems. We often hear changes in the environment, such as shifts in bird calls, before we see them. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has recently formed a sound charter to promote awareness of sound as a critical signifier in environmental health and urban planning.

I have spent decades making field recordings in which I create a setup before dawn or dusk, then lie on the ground listening for several uninterrupted hours. These projects have taught me how the density of the air changes as the sun rises or sets, how animal behavior shifts as a result, and how all of these things are intricately linked.

For example, sound travels further through denser material, such as cold air, than through warm summer air. Other factors, such as changes in a forest’s foliage density from spring to fall, also change a site’s reverberation characteristics. Exploring these qualities has led me to think about how perceptual measures of sound inform our understanding of environmental health, opening a new angle of inquiry around psychoacoustic properties of environmental sound.

Coyotes in Usery Mountain Regional Park, Arizona. Garth Paine

Altering sound environments affects survival

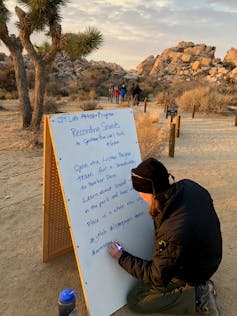

To engage the public and scientific communities in this research, the Acoustic Ecology Lab embarked in 2014 on a large-scale, crowd-sourced project teaching listening skills and sound recording techniques to communities adjacent to national parks and national monuments in the southwestern United States. After completing a listening and field recording workshop, community members volunteer to record at fixed locations in the parks every month, building a large collection of sound captures that is both a joy to listen to and a rich source of data for scientific analysis.

Imagine how climate change could affect environments’ sonic signatures. Reduced plant density will change the balance between absorptive surfaces, such as leaves, and reflective surfaces such as rocks and buildings. This will increase reverberation and make sound environments more harsh. And we can capture it by making repeated sound recordings at research sites.

In settings where sound reverberates for a long time, such as a cathedral, it can become tiring to carry on a conversation as echoes interfere. Increasing reverberation could have a similar effect in natural settings. Native species could struggle to hear mating calls. Predators could have difficulty detecting prey. Such impacts could spur populations to relocate, even if an area still offers plentiful food and shelter. In short, the sonic properties of environments are crucial to survival.

Listening can also promote stewardship. We use the recordings that our volunteers produce to create musical works, composed using only the sounds of the environment, which are performed in the communities that made the recordings. These events are a wonderful tool for mobilizing people around the issue of climate change impacts.

Mapping sound and weather characteristics

I also lead a research project called EcoSonic, which asks whether psychoacoustic properties of environmental sound correlate with weather conditions. If they do, we want to know whether we can use models or regular sound recordings to predict long-term impacts of climate change on the acoustic properties of environments.

This work draws on psychoacoustics – the point where sound meets the brain. Psychoacoustics is applied in research on speech perception, hearing loss and tinnitus, or ringing in the ears, and in industrial design. Until now, however, it has not been applied broadly to environmental sound quality.

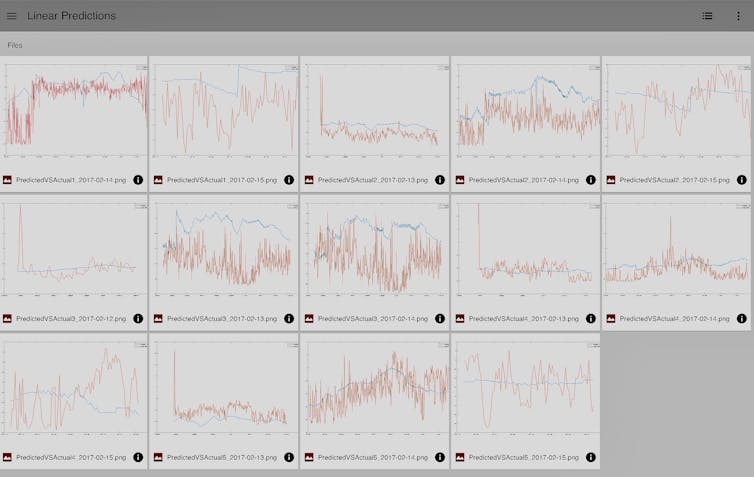

We use psychoacoustic analysis to assess qualitative measures of sound, such as loudness, roughness and brightness. By measuring the number of unique signals at a specific location, we can create an Acoustic Diversity Index for that place. Then we use machine learning – training a machine to make predictions based on past data – to model the correlation between local weather data and the Acoustic Diversity Index.

Our initial tests show a positive, statistically significant relationship between acoustic diversity and cloud cover, wind speed and temperature, meaning that as these variables increase, acoustic diversity does too. We also are finding an inverse, statistically significant relationship between acoustic diversity and dewpoint and visibility: As these factors increase, acoustic diversity decreases.

Sounding futures: Art, science and community

Sound quality is critical to our everyday experience of the world and our well-being. Research at the Acoustic Ecology Lab is driven from the arts and based on sensed experience of being present, listening, feeling the density of the air, hearing clarity of sound and perceiving variations in animal behavior.

Without the arts we would not be asking these perceptual questions. Without science we would not have sophisticated tools to undertake this analysis and build predictive models. And without neighboring communities we would not have data, local observations or historical knowledge of patterns of change.

All humans have the capacity to pause, listen and recognize the diversity and quality of sound in any given space. Through more active listening, each of us can find a different connection to the environments we inhabit.

Garth Paine, Associate Professor of Digital Sound and Interactive Media, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.