David S. Meyer, University of California, Irvine

A gaggle of young activists recently paid Dianne Feinstein a visit at the senator’s San Francisco office, imploring her to support the Green New Deal framework for confronting climate change. She responded by explaining the complicated legislative process, emphasizing her decades of experience and promising to pursue a considerably more modest approach to confronting climate change with a better shot at passage in the Senate.

The lawmaker tried to come across as sympathetic, yet sounded condescending in a short video clip that quickly went viral, eliciting a stream of criticism. A longer version told a more nuanced story, including why she believes her own “responsible resolution” has a better chance of passage.

It’s easy to understand why Feinstein’s confrontation went viral. Saying “no” to earnest children who see their futures in jeopardy makes politicians look callous.

Although the advent of social media has made it easier for millions to witness these awkward encounters, there is nothing new about kids engaging in grassroots activism. And based on my research about social movements, I find that today’s young activists have a lot in common with the leaders of earlier youth movements.

Young people often appear at the front lines of social change for three main reasons.

1. Passionate about causes

First, young people may refuse to ignore injustices or wait patiently when they feel passionately about a cause. That means they’re more apt to take risks.

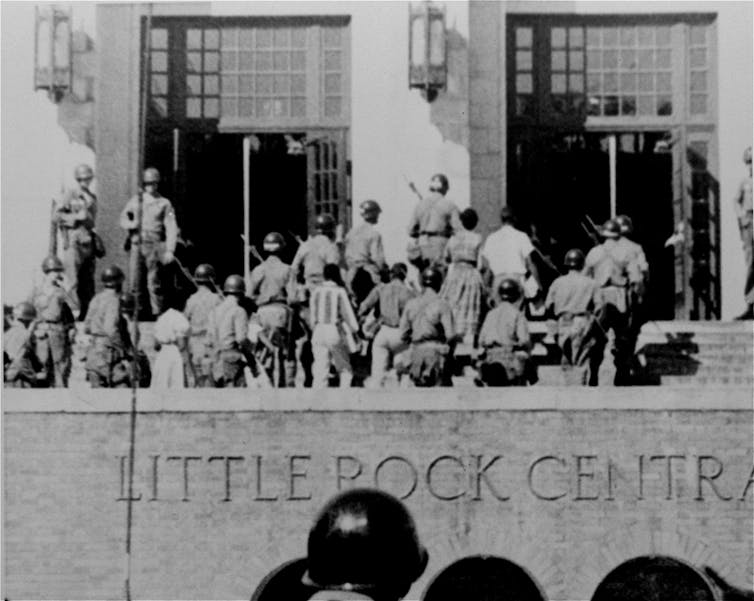

During the civil rights era, Ernest Green, Thelma Mothershed and seven other children known as the “Little Rock Nine” followed federal troops past jeering crowds of white teens to integrate Central High School in Arkansas in 1957.

More than 60 years later, the dean of students at a public high school less than an hour from Little Rock paddled three high school students for walking out of school to protest gun violence.

In both instances, young activists took risks that would scare off most adults.

2. Dramatic images

Second, politically engaged young people can create dramatic and appealing images to dramatize their cause. That’s what happened when Martin Luther King Jr. put schoolchildren at the front of a march for civil rights through Birmingham, Alabama. He surely knew they were likely to face police willing to use firehoses and dogs to disperse the crowds.

The visuals horrified the nation and inspired more action not only in the streets but in Congress – which passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 soon after that showdown.

Similarly, Jefferson County, Colorado high school students walked out of school in 2014 to campaign against their new school board’s promise to stop offering an advanced placement course in American history because these officials said its curriculum undermined patriotism. Some of the students must have read ahead in the text, for they carried placards with slogans like “There is nothing more patriotic than protest.”

3. Dilemmas for authorities

Third, dismissing or attacking young activists who appear earnest and sincere can prove perilous.

When Birmingham’s children’s march was met with police violence, national attention forced civil rights to the top of the White House’s agenda. It also cost Bull Connor, Birmingham’s public safety commissioner, his job.

Before Feinstein’s awkward encounter went viral, Fox News host Laura Ingraham experienced a similar snafu when she ridiculed gun-control activist David Hogg. The pundit teased the Parkland shooting survivor after he didn’t get into any of the four California universities at the top of his list, a move widely perceived as bullying.

Hogg’s youth made it tough for Ingraham to attack him. His political savvy made it even tougher when he tweeted the names of Ingraham’s sponsors, and suggested his supporters boycott her show. Ingraham eventually apologized, but only after losing some sponsors.

Hogg won this political standoff and even more. He will enroll at Harvard University in the fall of 2019 – along with Jaclyn Corin, a fellow Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School graduate and March for Our Lives co-founder.

Sunrise movement

The young activists who caught Feinstein off-guard, and another group that got arrested for trying to discuss climate policy with Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, belong to the Sunrise Movement. The relatively new group describes itself as an “army of young people.”

Like other youngsters before them, its members claim to have greater stake in forceful environmental action than their elders. Unlike many of the adults who call the shots on policy, they expect to be around to face the consequences should their leaders keep failing to take forceful action on climate change.

American kids and young adults are making these claims not only in the halls of Congress but also in court. More than 20 young people are plaintiffs in a federal lawsuit, Juliana v. U.S., that aims to force the government to slash the emissions that cause climate change.

Young people around the world, led by Swedish teen Greta Thunberg, are also organizing “climate strikes,” where young people will skip school to discuss the urgency of doing more about climate change and protest how little progress the authorities have made.

On March 15, tens of thousands of U.S. children plan to take part in a global action by walking out of schools. Large numbers of European students are already staging similar events.

Some critics are arguing that these young activists are serving as pawns of manipulative adults who are eager to use fresh faces to tout their own cause. The writer Caitlin Flanagan dismissed them as “jackbooted tots and aggrieved teenagers” and Feinstein referred to “whoever sent you here” during her brush with the Sunrise Movement.

But as sociologist Rebecca Klatch has found, teen activists have historically tended to echo their parents’ views authentically, just with more energy and enthusiasm.![]()

David S. Meyer, Professor of Sociology, University of California, Irvine

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.