An interview with Andra Yeghoian

By Carl Smith

Andra Yeghoian is the Environmental Literacy Coordinator at the San Mateo County Office of Education. She provides leadership in implementing a broad Environmental Literacy Initiative across San Mateo County. Andra has over 15 years of experience in education across public and private school systems, nationally and internationally. She holds a B.A. in International Relations and a Teaching Credential from UC Davis, and an MBA in Sustainable Systems from Pinchot University (Presidio Graduate School) in Seattle, Washington.

In a Green Technology interview, she offers insight into some of the innovative and effective ways that San Mateo County is addressing state mandates to cultivate environmental literacy.

How would you describe your role at the San Mateo County Office of Education?

There are 58 county offices that support all the school districts within our counties. A county office has regulatory functions and also leadership functions. Although the state has environmental literacy built into education code, my work is less regulatory and more sits in the spot of leadership and trying to help districts in our county to get on board with the work. It’s not just our job to inspire and to serve as a catalyst, but also to provide backbone support to all the school districts for bringing environmental literacy into their school. I think the backbone support piece is really critical because we’re saying, “We’re investing in providing resources to you, having some expertise and being a place where you can come to get the support that you need to move you along in your work.”

You were the first person ever hired at the county level to do this kind of work. Why was this the right time for the county to create such a position?

The San Mateo County superintendent, Anne Campbell, was getting a little bit of pressure from her board of education to do more in terms of greening the facilities our county office and to bring environmental topics more directly into schools. Then Ten Strands came to our county to offer professional development programs, to help teachers build units of study related to local environmental phenomena.

Both of those things were happening right around the same time in 2015. At that same time, the Blueprint for Environmental Literacy was being written. Because Anne showed interest in the teacher fellowship program and was really listening to the board about moving efforts forward in the operations, the state became interested in having her be a part of the steering committee for the blueprint. Multiple voices were saying, “This is important and we should invest,” and so she decided to do that.

At the governmental level, our county was being looked at as a really important county for having a conversation around climate change, because we have so many climate change pressures. We have the ocean on one side, the bay on the other. We have forest areas in our county. We have high heat, and high-density urban populations up towards the north in Daly City. We also have a strong agricultural base. Pretty much all our county will feel the impact, or is already feeling the impacts, of climate change. The state was looking towards our county as an area that really needs to have climate change adaptation and climate change mitigation as a major priority. With that background context, it makes sense why San Mateo County is a leader in this work.

As a result of your work, other educational agencies have begun to follow San Mateo’s example and are hiring educators to do similar work. Why might that be?

Some of that speaks to the K-12 education system recognizing what’s going on in other industries. Hiring environmental sustainability coordinators or directors, or just having a person like a chief sustainability officer, is becoming more and more common in business. Many universities and higher education institutions have a sustainability director or sustainability coordinator. That’s also true in government agencies; many cities and counties and state agencies now have some level of sustainability coordinator in place. I think K-12 systems were looking at that and recognizing that there’s a major shift happening across the board in other industries. We need to respond as well.

That’s one reason. Another reason is getting a call to action from youth. Youth have really made it clear in the last couple of years that this is an important issue. It’s important enough that youth across the world are walking out of classes and saying, “You must teach us about climate change. You have to do things about climate change, because this is the most important issue of our generation.”

There was also a call to action from our own state standards and from our own education code, having environmental literacy and the Environmental Principles and Concepts embedded in the Next Generation Science Standards framework, the health framework, the history and social studies frameworks. SB 720, basically said, “This needs to happen. This is part of what’s required in education.”

It’s our job at county offices to respond to the state mandates and to support our districts in achieving them. If we’re mandated to be teaching about the environment and we have mandates on green facilities, then we really need support from county offices of education to be able to execute on those mandates.

What makes up a systemic approach to environmental literacy?

What makes up a systemic approach to environmental literacy?

There are two different elements to the systemic approach. One element is the idea of backbone support coming at different scales. We’ve got backbone support coming from Ten Strands at the state level, supporting work with funding, supporting work with incremental change, and really serving as a state-wide catalyst. Then scale that down to the regional level and we have county offices of education that provide the backbone support. Then, ideally, you’d also have each district having some level of backbone support, like a sustainability coordinator.

We’re starting to see that shift happen. Momentum for the work can build much faster when you have that level of systemic support. Then there’s a different level, which is what this looks like across the whole school.

The systemic approach at a school level is the idea of “whole-school” sustainability. That involves what I call the “Four Cs” of sustainability. The first is doing the work on your campus, with green operations and facilities. Then there’s bringing environmental topics and issues into the curriculum.

Next is community engagement, walking the talk of sustainability and working with the external community to have great community partnerships. Those are three of the Cs, and when you do things across your campus, in your curriculum and in your community engagement programming you’re really going to see an overall shift in your culture. That’s the fourth C, the idea of shifting the culture of the school.

The systemic approach at the site level is really thinking about how environmental sustainability touches all facets of the institution and how it connects to everything that happens on a daily basis at school.

I started this work in the classroom. I really saw that, as a teacher, I could be a change agent. Then I became a sustainability director at a school site. I saw what it looks like to do this at the whole-school level. Now I’m at the county, supporting the districts and looking at how the districts can be change agents.

If environmental principles and concepts are embedded in the state’s education code, it’s not really “optional” to include them in curriculum. Even if that weren’t the case, how important is the work that you’re doing to the educational mission of schools?

I’m a little bit biased because I believe so strongly in this work, but we are using the philosophy at our school that the world becomes what we teach. I think that that’s really, really true. In the past, environmental literacy has not been a critical part of K-12 education and look at what the world has become. We are ripe with tons of environmental problems and issues, and we’re just waking up to their urgency. We need to have a population that’s environmentally literate if we want to solve these problems.

I feel very strongly that we have a moral calling to include environmental literacy in all things that our school provides. I’m so grateful that we have legislators who recognize the importance of it and who decided, “Let’s turn that moral calling into actual policy.”

I can give a concrete example. Last week, I was running a zero-waste institute and looking at some of the data around waste. I found that globally, we are diverting our waste at a very, very low rate. Globally, we’re diverting waste to recycling and compost at a rate of 15 percent. I looked at the current statistics for schools, and it was exactly the same. We are only diverting waste to recycling and compost a rate of 15 percent, and sending 85 percent of the waste in a school waste stream to the landfill, even though we could recycle and compost 92 percent of what is in a school’s waste stream.

For me, that was such an important statistic. Literally, the world has become what we teach. We don’t teach about waste, and look at what happens: we don’t divert our waste.

What’s an example of something that has been put in place that is really working?

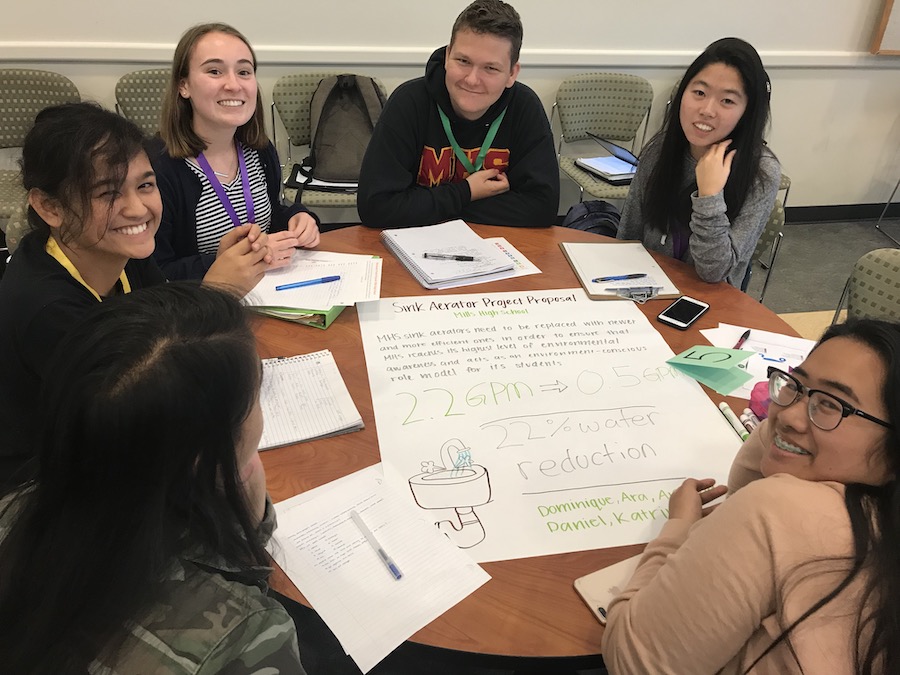

We are in the fifth year of running a teacher professional development program, the San Mateo Environmental Learning Collaborative (SMELC). The premise of this program is to build the capacity of our teachers to design and implement units of study that start with students identifying a local environmental issue and then getting to the level of solving it through advocacy and action. That solutionary, action and advocacy-based approach has been really, really successful.

Teachers who complete that program feels a strong sense of, “I’ve been transformed. I will never teach again without including the environment.” The reason that they say that is because their kids responded so positively, they just came alive during these units.

The major components of this type of learning are getting kids outside and helping foster love, wonder and stewardship for nature. Another component is utilizing the campus and the community as a laboratory for learning. These are strong examples of environmental literacy, getting kids outside doing place-based, local context learning that really leverages our campus and our community and creates a lab for learning and for civic engagement.

Are you finding that students and teachers lessons respond differently to lessons that address these topics? Do they touch a nerve in any way, or is just another day at school?

Research has been conducted looking at environmental education in many, many different communities. It shows that when you support your students’ ability to develop environmental literacy and an environmental lens, it’s a win-win in all ways.

It helps them academically. It helps them emotionally. It helps them feel more connected to their community. Kids want to be at school when they’re doing these types of things. We’re seeing major gains for populations that have otherwise had a major achievement gap—English language learners, for example. Oftentimes, we’re seeing students who haven’t had a chance before being able to engage with the material during these lessons in a way that’s been really successful for them.

When you bring a kid outside and you ask them to just make observations, like “Draw pictures. What do you see? What do you wonder?”, it invites students who otherwise would have just been handed a text in a classroom and struggled through that text to really engage. Making observations is something that anybody can do, regardless of language acquisition or reading level. We’re finding that students really do respond differently to this kind of teaching and we’re seeing major academic gains for populations that have otherwise struggled.

We’re also seeing changes in students who had felt marginalized in their school, even some of our most vulnerable students, like kids who are in our court and community schools, our juvenile hall system or foster kids. When environmental literacy has been brought into their education experience, many, many of these students are saying things like, “For the first time I felt like I came alive in my classroom,” or “I recognize that these are career pathways for me. I’m so grateful that I’m learning about something where I can see myself, and see a future pathway into college and a career.”

There’s increasing interest in finding the learning opportunities in facility projects – energy efficiency, solar power, water conservation, etc. How important is it to capture these opportunities?

These things go hand in hand. I think it is impossible to do environmental literacy well if you are not making efforts in your facilities and operations. Kids will look at that and they’ll be like, “Great, I hear you talking about the environment,” but if we don’t have a compost bin or some level of solar panels, or green purchasing for our energy sources, kids will recognize that we’re not walking the talk.

Facility projects are critical to learning. They offer kids a chance to look at real-world data and really see that impact happen. If you don’t already have green facilities measures in place, it’s still an opportunity for kids to look at real-world data, look at a problem and then get a chance to solve it and look at their own impact when they’ve solved it on their own campus. I think that is super awesome.

Have you seen any examples of a better outcome from an energy, water or other program because the kids were involved in a learning opportunity around it?

I have for, for certain. When I was a site level director of sustainability, we wrapped a lot of our environmental literacy efforts around what we were doing on the campus. For example, our Algebra One class studied all of the green facilities and operations efforts and a return on investment analysis. They came to the realization that, “We haven’t reduced our greenhouse gas emissions enough because it turns out our transportation and our commuting to school actually has a much larger greenhouse gas emissions footprint than our energy use. So yes, continue to do invest in solar and energy efficiency, but let’s shift gears and put some effort into a carpooling campaign and a walking and rolling to school campaign, so we reduce those greenhouse gas emissions.” It was something that students came up with themselves, seeing that we were doing great things, but not seeing the results that we wanted because we weren’t necessarily targeting the right area.

Are there benefits to companies in the schools space from being aware of this trend? Would it be of value to schools and teachers if these companies had their own sense of the learning opportunities present in projects that use their products?

I definitely think so. Let’s use refillable water bottle stations as an example. You can bring in a refillable water bottle station and have no educational awareness around it. But something some of the companies have done is to provide users information about how many bottles have been reduced from the environment. Every single time somebody fills up their water bottle, they are being educated to remember, “Your action right now is saving the planet, and it collectively, this many bottles have been saved by everybody else who decided to do this.”

Whatever your product is, having whatever mission you have for the planet somehow articulated on your product is critical, I think. That’s a very, very simple step that companies can take, to just label their products with some level of education. Then there could also be an associated lesson that could go along with it. Then we could say, “Hey, we just got this new thing at our school. Let’s have a lesson around why this particular thing is so important.”

I would encourage companies to think about how could a lesson be done in a classroom. It can be done the first year that a product is introduced. Then there could be a lesson that can be used every single year, one where every freshman, or every sixth grader or every third grader learns about this one thing and why it’s so important.

How far can the benefits of developing environmental literacy in students extend? Is it going too far to suggest it could give students the ability to “read” their world, just as they would read a book?

No. I think that nails it. I taught geography and I remember working on map literacy. Once you have the skills of reading a map and really understanding spatial awareness, you are spatially and geographically literate. Your navigation abilities are going to be so much better. Anywhere you go, you’re just going to have a stronger sense of how to navigate the world.

When it comes to environmental literacy, we’re trying to support having a population that can they look at trees, and look at other species, and see the importance of them. They have the literacy to know, “I rely on that living species for my survival and we have a relationship that’s interdependent. Therefore, I cannot let my impact be so much that it damages that thing because when I do that, it’ll circle back and damage me.”

That’s the foundation of being environmentally literate. It’s understanding how to read the relationship between the natural world and the human-built world and understanding that they have to be in balance.

Is there anything else that you would want to say to colleagues or others involved in education?

There are just two things. One is that climate change is here. We are experiencing the impacts of climate change, whether that’s drought, whether that’s heat waves, whether that’s a fire, a flood, a massive storm or an agriculture base collapsing. We are experiencing that all over the world and we are experiencing it more and more in California communities. That level of disruption and that level of disasters comes with a lot of trauma. We’re seeing trauma unfold in a way that is unprecedented and educators are to bear the brunt of carrying the emotions of the adults and the children in the community in dealing with the trauma of environmental degradation.

This is just another piece that educators need to consider when they think about supporting their kids and their emotional and social well-being. Trauma informed practices are absolutely critical when it comes to understanding how to make space for grappling with the emotions of things like a community being devastated by fire or having schools closed because pollution has made the air unsafe to breathe.

The other is the major call to action that I believe needs to be felt by all educators. We are in a critical time in all of human existence, where we need to make a major fundamental shift towards the sustainable paradigm. Our window of time to make that transformational shift is very, very short. I hate to sound so radical, but my hope and dream is for all educators in the K-12 system to recognize the fundamental importance of their role in saving the world.

I always like to position environmental literacy as an opportunity to have classrooms save the world, to have people look back and they say, “Oh my gosh, educators are our greatest heroes because they stepped up at this critical moment and shifted the minds of all humans, to help them understand that we need to live in a different way.”

I really want educators to know that they have a call to action and they must respond.

I would go a little further on that. Status quo is not an option. Status quo will lead us to our extinction. We have to make a change, and educators are a part of that change.

Thank you