Jeremiah Johnson, North Carolina State University and Joseph F. DeCarolis, North Carolina State University

Due to their decreasing costs, lithium-ion batteries now dominate a range of applications including electric vehicles, computers and consumer electronics.

You might only think about energy storage when your laptop or cellphone are running out of juice, but utilities can plug bigger versions into the electric grid. And thanks to rapidly declining lithium-ion battery prices, using energy storage to stretch electricity generation capacity.

Based on our research on energy storage costs and performance in North Carolina, and our analysis of the potential role energy storage could play within the coming years, we believe that utilities should prepare for the advent of cheap grid-scale batteries and develop flexible, long-term plans that will save consumers money.

Peak demand is pricey

The amount of electricity consumers use varies according to the time of day and between weekdays and weekends, as well as seasonally and annually as everyone goes about their business.

Those variations can be huge.

For example, the times when consumers use the most electricity in many regions is nearly double the average amount of power they typically consume. Utilities often meet peak demand by building power plants that run on natural gas, due to their lower construction costs and ability to operate when they are needed.

However, it’s expensive and inefficient to build these power plants just to meet demand in those peak hours. It’s like purchasing a large van that you will only use for the three days a year when your brother and his three kids visit.

The grid requires power supplied right when it is needed, and usage varies considerably throughout the day. When grid-connected batteries help supply enough electricity to meet demand, utilities don’t have to build as many power plants and transmission lines.

Given how long this infrastructure lasts and how rapidly battery costs are dropping, utilities now face new long-term planning challenges.

Cheaper batteries

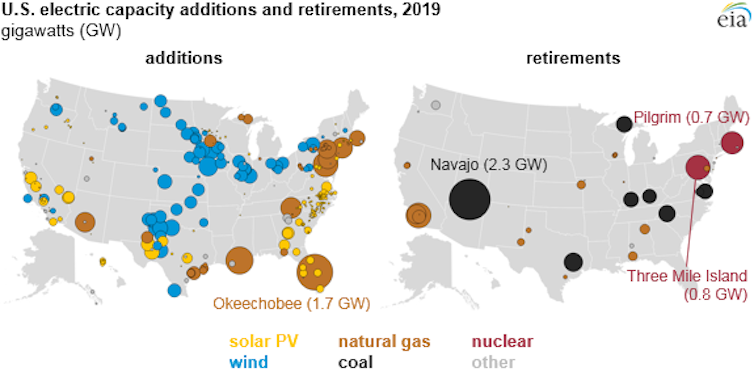

About half of the new generation capacity built in the U.S. annually since 2014 has come from solar, wind or other renewable sources. Natural gas plants make up the much of the rest but in the future, that industry may need to compete with energy storage for market share.

In practice, we can see how the pace of natural gas-fired power plant construction might slow down in response to this new alternative.

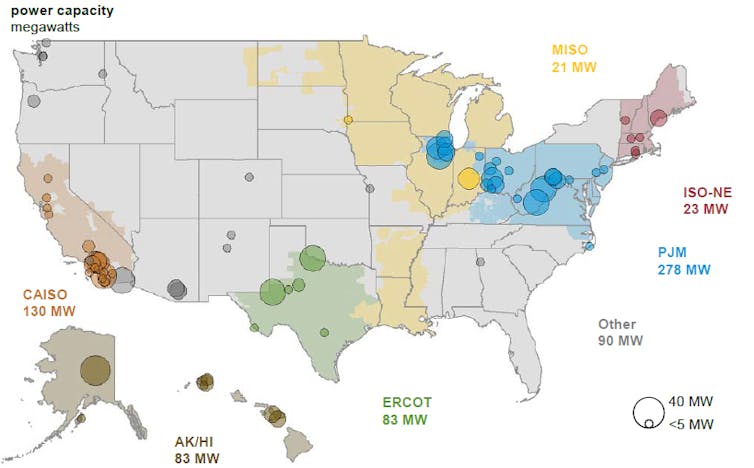

So far, utilities have only installed the equivalent of one or two traditional power plants in grid-scale lithium-ion battery projects, all since 2015. But across California, Texas, the Midwest and New England, these devices are benefiting the overall grid by improving operations and bridging gaps when consumers need more power than usual.

Based on our own experience tracking lithium-ion battery costs, we see the potential for these batteries to be deployed at a far larger scale and disrupt the energy business.

When we were given approximately one year to conduct a study on the benefits and costs of energy storage in North Carolina, keeping up with the pace of technological advances and increasing affordability was a struggle.

Projected battery costs changed so significantly from the beginning to the end of our project that we found ourselves rushing at the end to update our analysis.

Once utilities can easily take advantage of these huge batteries, they will not need as much new power-generation capacity to meet peak demand.

Utility planning

Even before batteries could be used for large-scale energy storage, it was hard for utilities to make long-term plans due to uncertainty about what to expect in the future.

For example, most energy experts did not anticipate the dramatic decline in natural gas prices due to the spread of hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, starting about a decade ago – or the incentive that it would provide utilities to phase out coal-fired power plants.

In recent years, solar energy and wind power costs have dropped far faster than expected, also displacing coal – and in some cases natural gas – as a source of energy for electricity generation.

Something we learned during our storage study is illustrative.

We found that lithium ion batteries at 2019 prices were a bit too expensive in North Carolina to compete with natural gas peaker plants – the natural gas plants used occasionally when electricity demand spikes. However, when we modeled projected 2030 battery prices, energy storage proved to be the more cost-effective option.

Federal, state and even some local policies are another wild card. For example, Democratic lawmakers have outlined the Green New Deal, an ambitious plan that could rapidly address climate change and income inequality at the same time.

And no matter what happens in Congress, the increasingly frequent bouts of extreme weather hitting the U.S. are also expensive for utilities. Droughts reduce hydropower output and heatwaves make electricity usage spike.

The future

Several utilities are already investing in energy storage.

California utility Pacific Gas & Electric, for example, got permission from regulators to build a massive 567.5 megawatt energy-storage battery system near San Francisco, although the utility’s bankruptcy could complicate the project.

Hawaiian Electric Company is seeking approval for projects that would establish several hundred megawatts of energy storage across the islands. And Arizona Public Service and Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority are looking into storage options as well.

We believe these and other decisions will reverberate for decades to come.

If utilities miscalculate and spend billions on power plants it turns out they won’t need instead of investing in energy storage, their customers could pay more than they should to keep the lights through the middle of this century.![]()

Jeremiah Johnson, Associate Professor of Environmental Engineering, North Carolina State University and Joseph F. DeCarolis, Associate Professor of Environmental Engineering, North Carolina State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.