By Jennifer Francis, Rutgers University

Damage from extreme weather events during 2017 racked up the biggest-ever bills for the U.S. Most of these events involved conditions that align intuitively with global warming: heat records, drought, wildfires, coastal flooding, hurricane damage and heavy rainfall.

Paradoxical, though, are possible ties between climate change and the recent spate of frigid weeks in eastern North America. A very new and “hot topic” in climate change research is the notion that rapid warming and wholesale melting of the Arctic may be playing a role in causing persistent cold spells.

It doesn’t take a stretch of the imagination to suppose that losing half the Arctic sea-ice cover in only 30 years might be wreaking havoc with the weather, but exactly how is not yet clear. As a research atmospheric scientist, I study how warming in the Arctic is affecting temperature regions around the world. Can we say changes to the Arctic driven by global warming have had a role in the freakish winter weather North America has experienced?

A ‘dipole’ of abnormal temperatures

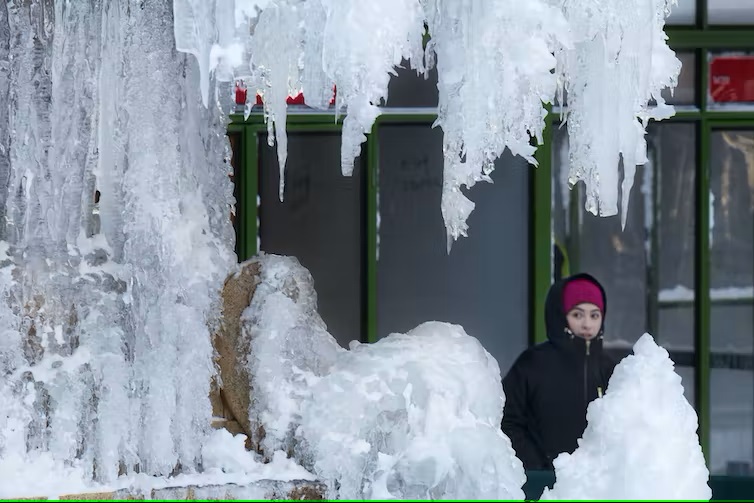

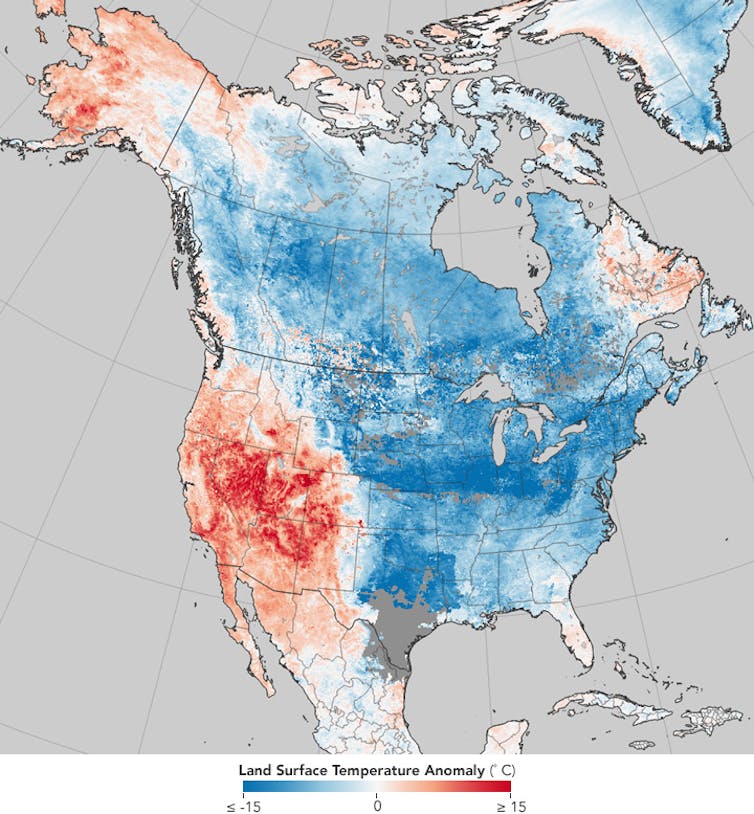

Weird and destructive weather was in the news almost constantly during 2017, and 2018 seems to be following the same script. Most U.S. Easterners shivered their way through the end of 2017 into the New Year, while Westerners longed for rain to dampen parched soils and extinguish wildfires. Blizzards have plagued the Eastern Seaboard – notably the “bomb cyclone” storm on Jan. 4, 2018 – while California’s Sierra Nevada stand nearly bare of snow.

This story is becoming a familiar one, as similar conditions have played out in four of the past five winters. Some politicians in Washington D.C., including President Trump, have used the unusual cold to question global warming. But if they looked at the big picture, they’d see that eastern cold spells are a relative fluke in the Northern Hemisphere as a whole and that most areas are warmer than normal.

A warm, dry western North America occurring in combination with a cold, snowy east is not unusual, but the prevalence and persistence of this pattern in recent years have piqued the interests of climate researchers.

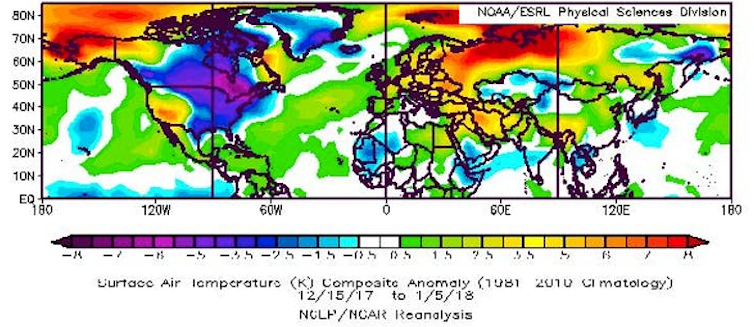

The jet stream – a fast, upper-level river of wind that encircles the Northern Hemisphere – plays a critical role. When the jet stream swoops far north and south in a big wave, extreme conditions can result. During the past few weeks, a big swing northward, forming what’s called a “ridge” of persistent atmospheric pressure, persisted off the West Coast along with a deep southward dip, or a “trough,” over the East.

New terms have been coined to describe these stubborn features: “The North American Winter Temperature Dipole,” the “Ridiculously Resilient Ridge” over the West, and the “Terribly Tenacious Trough” in the East.

Regardless what it’s called, this dipole pattern – abnormally high temperatures over much of the West along with chilly conditions in the East – has dominated North American weather in four of the past five winters. January 2017 was a stark exception, when a strong El Niño flipped the ridge-trough pattern, dumping record-breaking rain and snowpack on California while the east enjoyed a mild month.

Two other important features are conspicuous in the dipole temperature pattern: extremely warm temperatures in the Arctic near Alaska and warm ocean temperatures in the eastern Pacific. Several new studies point to these “ingredients” as key to the recent years with a persistent dipole.

It takes two to tango

What role does warming – specifically the warming ocean and air temperatures in the Arctic – play in this warm-West/cool-East weather pattern? The explanation goes like this.

Pacific Ocean temperatures fluctuate naturally owing to short-lived phenomena such as El Niño/La Niña and longer, decades-length patterns. Scientists have long recognized that those variations affect weather patterns across North America and beyond.

The new twist in this story is that the Arctic has been warming at at least double the pace of the rest of the globe, meaning that the difference in temperature between the Arctic and areas farther south has been shrinking. This matters because the north/south temperature difference is one of the main drivers of the jet stream. The jet stream creates the high- and low-pressure systems that dictate our blue skies and storminess while also steering them. Anything that affects the jet stream will also affect our weather.

When ocean temperatures off the West Coast of North America are warmer than normal, as they have been most of the time since winter 2013, the jet stream tends to form a ridge of high pressure along the West Coast, causing storms to be diverted away from California and leaving much of the West high and dry.

If these warm ocean temperatures occur in combination with abnormally warm conditions near Alaska, the extra heat from the Arctic can intensify the ridge, causing it to reach farther northward, become more persistent, and pump even more heat into the region near Alaska. And in recent years, Alaska has experienced periods of record warm temperatures, owing in part to reduced sea ice.

My colleagues and I have called this combination of natural and climate change-related effects “It Takes Two to Tango,” a concept that may help explain the Ridiculously Resilient Ridge observed frequently since 2013. Several new studies support this human-caused boost of a natural pattern, though controversy still exists regarding the mechanisms linking rapid Arctic warming with weather patterns farther south in the mid-latitudes.

More extreme weather ahead?

In response to the strengthened western ridge of atmospheric pressure, the winds of the jet stream usually also form a deeper, stronger trough downstream. Deep troughs act like an open refrigerator door, allowing frigid Arctic air to plunge southward, bringing misery to areas ill-prepared to handle it. Snowstorms in Texas, ice storms in Georgia and chilly snowbirds in Florida can all be blamed on the Terribly Tenacious Trough of December 2017 and January 2018.

Adding icing on the cake is the tendency for so-called “nor’easters,” such as the “bomb cyclone” that struck on Jan. 4, to form along the East Coast when the trough’s southwest winds align along the Atlantic Seaboard. The resulting intense contrast in temperature between the cold land and Gulf Stream-warmed ocean provides the fuel for these ferocious storms.

The big question is whether climate change will make dipole patterns – along with their attendant tendencies to produce extreme weather – more common in the future. The answer is yes and no.

It is widely expected that global warming will produce fewer low-temperature records, a tendency already observed. But it may also be true that cold spells will become more persistent as dipole patterns intensify, a tendency that also seems to be occurring.

It’s hard to nail down whether this weather pattern – overall warmer winters in North America but longer cold snaps – will persist. Understanding the mechanisms behind these complex interactions between natural influences and human-caused changes is challenging.

![]() Nevertheless, research is moving forward rapidly as creative new metrics are developed. Our best tools for looking into the future are sophisticated computer programs, but they, too, struggle to simulate these complicated behaviors of the climate system. Given the importance of predicting extreme weather and its impacts on many aspects of our lives, researchers must continue to unravel connections between climate change and weather to help us prepare for the likely ongoing tantrums by Mother Nature.

Nevertheless, research is moving forward rapidly as creative new metrics are developed. Our best tools for looking into the future are sophisticated computer programs, but they, too, struggle to simulate these complicated behaviors of the climate system. Given the importance of predicting extreme weather and its impacts on many aspects of our lives, researchers must continue to unravel connections between climate change and weather to help us prepare for the likely ongoing tantrums by Mother Nature.

Jennifer Francis, Research Professor, Rutgers University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.